Corporate law and textiles would seem radically unrelated, but Delhi-based Krishna Sarma sure knows how to juggle her two passions. As a busy corporate lawyer, she specialises in the life sciences sector. As an Assamese lover of art and craft concerned about the plight of weavers in the Northeast, she constantly works to uplift conditions of artisans in the region.

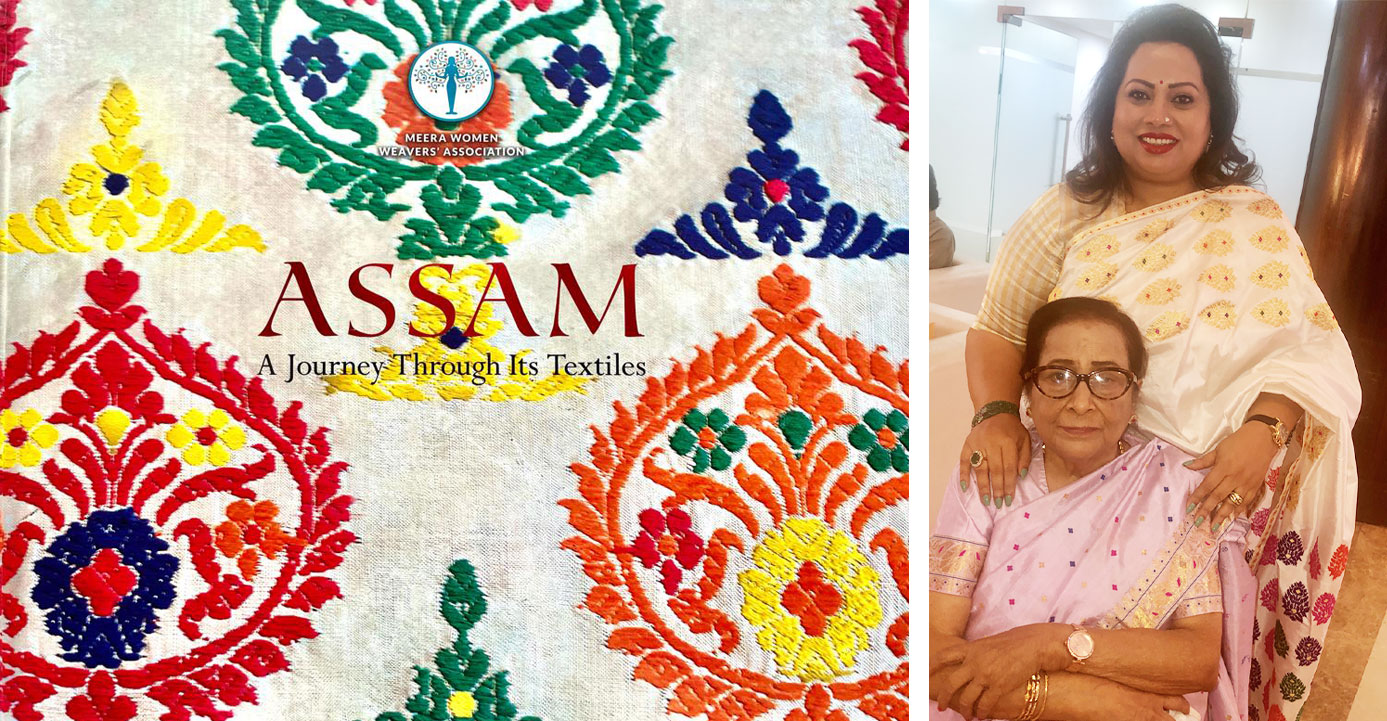

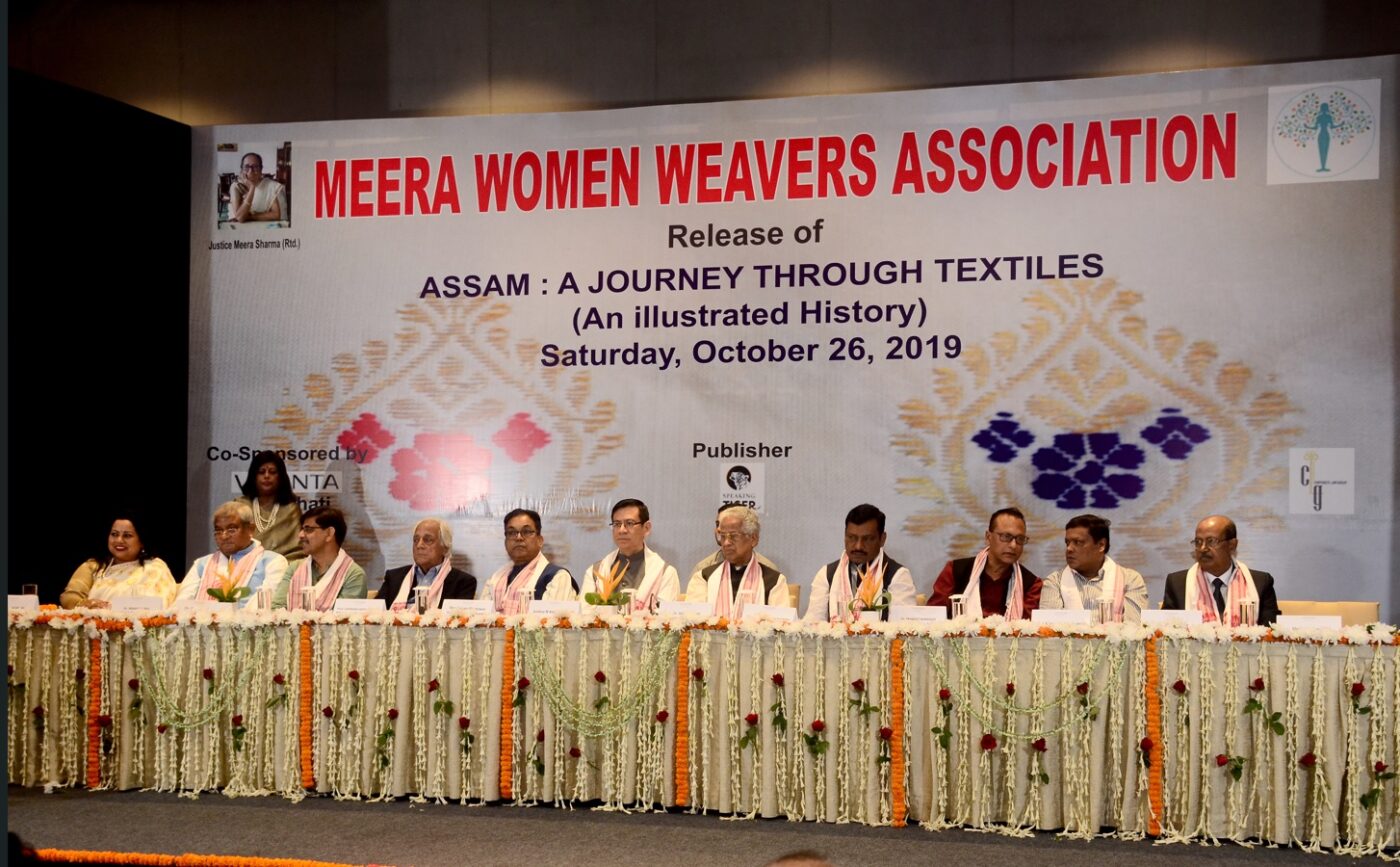

“These days, we all take on multiple roles. At times there are conflicts, but I prioritise as per the need of the hour,” says Sarma, about how she balances her acts. So far, she has managed impressively, too. Between power meetings and court cases as founder and managing partner at her law firm, she has co-authored a book title Assam: A Journey Through Its Textiles that beautifully documents the weaves and textiles of the state and she has also set up the Meera Women Weavers Association for the betterment of female weavers in Assam.

“I am a lawyer first and as managing partner of my law firm, I give priority to my profession and clients,” says Sarma, who set up the Corporate Law Group (CLG) in the Capital in 1998. Her credentials include serving as Additional Advocate General for the state of Assam in the Supreme Court from 2011 to 2016. She was Standing Counsel for the state from 2001 to 2016, too.

For Sarma, her calling as a lawyer and her love for the art and heritage of weaves are both rooted in her childhood. Born in Guwahati, she grew up in a close-knit family with four siblings, many cousins on both sides and neighbourhood friends. “I had a very happy childhood with all the small-town delights,” she says, adding: “All the festivals — except Durga Puja, when we used to visit our maternal grandparents in Nazira — were spent in Nalbari, at my paternal grandparents’ house.”

She recalls how life changed in 1983 when her father Bhupen Sharma, a lawyer and politician, passed away. “Within months my grandfather, Joydev Sharma, a renowned educationist, too, left us,” says Sarma. “It changed me. I became very responsible and serious.” It was left to her “exceptionally patient and courageous mother”, Justice Meera Sharma (retd.), a lawyer back then, to bring up the kids.

Years later, she would name Meera Women Weavers Association after her mother, as a tribute to her “grit and perseverance”. Sarma says of her mother: “She represented true women’s empowerment. She rebelled against her parents. Back in the era when the prevailing social norm was to get girls married off in their late teens, she chose to pursue higher studies and make a career for herself in law. My mom was the first woman in the Northeast to be a lawyer. She continues to be an inspiration for many generations of young women in the Northeast.”

Sarma, too, is among the many young women inspired by her mother, carving an academic track record of excellence before becoming an achiever on her own accord. She secured the fifth rank in her class 10 boards exams in the state merit list, studied law at the Campus Law Centre, University of Delhi, and had a stint working in a law firm in Washington DC before launching CLG in August 1998 in a basement with one client and a junior. “We now have a diverse clientele and we have a strong practice in commercial laws, regulated industries like bio-pharmaceuticals, intellectual property, and government policy,” she reveals with pride.

Sarma took out time from her busy schedule to engage in a conversation with The Northeast Stories

The book Assam: A Journey Through Its Textiles, which you have co-authored, documents the weaves and textiles of the state. What do you think can help to keep alive weaving, which is so intrinsic to the culture and heritage of the Northeast but is a dying craft for want of support and lack of market linkage?

Krishna Sarma: The tradition of spinning and handloom weaving has deep roots in Assam and the Northeast. Textiles are an important reference point and idiom for a culture where traditional textile is produced as an everyday activity in households and are worn by community members. However, Social mobility and acculturation induced by increased economic opportunities in recent decades has lent homogeneity to mass-produced, factory-made fabrics. This diminishes the unique cultural language of the tribes and their identifier markers that handloom and traditional weaving provides. In most tribes, there has been a rapid loss of indigenous designs and traditional textiles. While older women continue to wear simpler versions of traditional dresses, the younger generation is opting for contemporary clothes, reserving traditional dresses for ceremonial occasions.

Weaving is a multistage activity involving silkworm rearing, harvesting, spinning, dyeing, setting up the loom, preparing the warp, and weaving. Unfortunately, most girls no longer actively participate in these processes, leading to loss of hands at work and loss of skills. Colour palettes have changed with access to cheaper mill-made multi colored yarns and commercialisation has led to sourcing of finished traditional textiles from the southern states and China. There is a dilution of indigenous design languages.

Furthermore, weaving is not considered a viable economic activity. About 90 per cent of weavers in Assam are women who weave during their leisure time in order to supplement the household income and for their own use. The market is flooded with cheap factory products including the ubiquitous Assamese Gamosha! The lower productivity and the “laahe-laahe” Assamese attitude is a deterrent to productivity and output.

What are your thoughts on how to preserve traditional weaving practices?

Krishna Sarma: I am not an expert in this area but areas that demand attention would include skill development, design and product intervention, creation of well-resourced cooperative platforms run by weavers, financing support, providing quality and natural yarns through yarn banks, upgrade to fly-shuttle looms, introducing sustainable innovation and technology and handhold on the ability to access and compete in the marketplace. Such interventions can create new opportunities for employment in rural areas and empower rural women. In any successful enterprise, ownership and leadership is key and therefore empowering women at the grassroots is key. It is critical that the design traditions, fibres and motifs etc are documented and preserved. It is also important that we have dedicated textile museums to preserve and celebrate our textile heritage.

What inspired you to set up Meera Women Weavers Association (MWWA)?

Krishna Sarma: The name Meera Women Weavers Association is a tribute to my mother’s grit and perseverance.

I am passionate about gender equality and women’s empowerment, and I love traditional weaves and handlooms. Most handloom weavers are women. So, I decided why not to combine my cultural passions into an objective that aids women’s empowerment. Meera Women Weavers Association was established in 2016 as a not-for-profit institution, to join the efforts to document the oral and living handloom weaving traditions, techniques, motifs and traditional attires of the Assamese people. Second, the effort is to provide a cooperative and commercially profitable platform for women weavers to use their traditional expertise, allowing them to work at home while becoming breadwinners. It is also an endeavour to teach women how to navigate the digital marketplace.

Tell us about the private museum you were setting up. Is it ready?

Krishna Sarma: One of the ambitious future projects is to set up a textile museum and a retail experience outlet in Guwahati and, possibly, also in Delhi. Unfortunately, it is still at the idea stage.

What kind of additional source of livelihood are you providing to women weavers through the Association?

Krishna Sarma: Many years before MWWA, we started off in my father’s native district by experimenting with self-help women groups with the aim of empowering them, and also generating employment and income for rural women, under the aegis of the Bhupendra Nath Sharma (BNS) Foundation. BNS Foundation funded and trained women in select Nalbari villages to make them self-sufficient via mushroom farming besides stitching and sewing courses. During that process we realised many women in these villages already are producing exquisite handloom fabrics in their homes. We wanted to expand that and empower women not just in rural Nalbari but in the entire Seven Sister states.

We decided to do a thorough study of handloom textile traditions among tribes in Assam in particular, and the Northeast in general. The findings were captured in the book Assam: A Journey Through Its Textiles” in 2019. Plans were made to put into practice the findings of the experience and transform them into economically rewarding activities for women weavers. But then, as Robert Burns said: “The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry”. The pandemic of 2020 happened. So, unfortunately, owing to a busy work schedule, family commitments and the pandemic disruptions over the last two-and-a-half years, work on this project hasn’t progressed, apart from the Illustrated book. It looks like we will pick up the museum and the retail outlet work in 2023, top-down approach.

In 2007, you helped Assam Science Technology and Environment Council (ASTEC) obtain Geographical Indication protection for Muga silk, the pride of Assam. Tell us more about this.

Krishna Sarma: Muga silk is endemic to the Brahmaputra Valley. There are several wild and semi-domesticated varieties of muga. A special variety of muga silk known as Mejankari is reared on a chapa tree, indigenous to Assam, and considered superior in quality to the golden muga. It was preferred by the Ahom kings. My firm CLG and I practice in the area of Intellectual Property. In 2007, we helped ASTEC obtain Geographical Indication (GI) protection for Muga Silk of Assam. The logo was registered in 2013. The GI is a sign used on products that have a specific geographical origin and, importantly, possess qualities and a reputation that are due to that origin. The unique characteristics of muga silk are its everlasting and stable colour, the natural golden colour, which increases with each wash, a tensile strength of 4.53g/dn that makes it the strongest of all silks, its ultraviolet absorption capacity at about 80 per cent, its durability of over a hundred years and acid resistance. The GI protection has the potential to add value to muga products provided a quality-control mechanism is enforced.

Tell us about how you led the assamfloods.org advocacy effort to find a sustainable water management solution in the Brahmaputra basin?

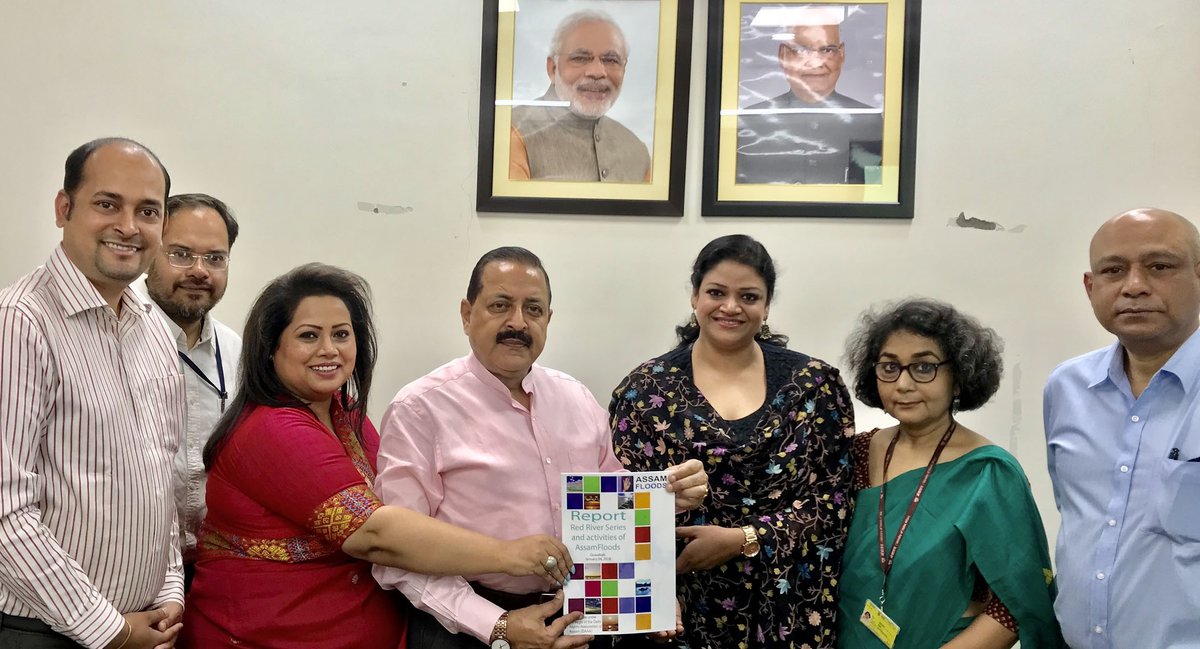

Krishna Sarma: Floods are an annual phenomenon in Assam and the Northeast during the monsoons, bringing massive disruption to people and the economy. The Brahmaputra in spate is a massive river in terms of discharge, one of the top 10 in the world. We pondered over what can be done to minimise the disruptions, which led to questions pertaining to why floods happen, how people’s sufferings be minimised, what we can learn of the root causes from the previous 100 years and if floods are inevitable what can be done to build resilience. The AssamFloods initiative was born from the need to find these answers, and taken under the aegis of the Delhi Alumni Association of Assam (DAAA), Delhi Chapter. In July 2017, AssamFloods, in association with Delhi Alumni Association of Assam, initiated the Red River Series of Talks where we invited leading experts to speak on various aspects of Brahmaputra Water Management. A report that appeared on AssamFloods was released by the Governor of the state in Guwahati on January 6, 2018. We have made several presentations highlighting 13 recommendations of the report to dignitaries including the Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (DONER) and a World Bank Team working on a report on the Brahmaputra Water Management. We also met Dr. Jitendra Singh, who was Minister of State, Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (DONER), and Sanjay Kundu, who was Joint Secretary (Policy & Planning), Ministry of Water Resources. Unfortunately, there has been little progress.

Tell us about your initiative of professionals from Assam in Delhi called Axom: New Horizons. Also, what other initiatives do you undertake with regard to the Northeast?

Krishna Sarma: Axom: New Horizons is an informal forum of like minded professionals from Assam who live in Delhi and includes achievers from publishing, bureaucracy, law, media, films, advertising, industry, entertainment and policymaking amongst others. The goal is to utilise the collective professional expertise, experiences and networks to put the spotlight on issues that affect Assam, help develop and advocate policy interventions for social and economic progress of Assam, and help preserve the state’s rich, diverse and unique cultural and linguistic heritage. In February 2018, Axom: New Horizons initiated the Series of Talks on the Northeast issues, highlighting the importance of projecting the Northeast and Assam in the right perspective. The group started work on revising its North Eastern Region Vision 2020 document but the progress got hampered due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

What should Northeast women living outside their states keep in mind, given there is tendency to misjudge them?

Krishna Sarma: The women of the Northeast are progressive, independent and industrious. We should celebrate that. There are elements of racism because of the way we look and our distinct cultures, but at the same time we, too, tend to be clannish. Our women doing well in sports are universally celebrated and it helps fight stereotypes. There needs to be understanding and acceptance on both sides.